Erin King scoots up to the operating table, where her patient is already situated in stirrups, a bright light beaming over both of them. “How far did you have to travel to be here today?” King asks, her voice calm and upbeat as she begins the abortion procedure. The 21-year-old woman stares up at the ceiling, gently gripping a nurse’s hand. She says she and her boyfriend drove overnight from Oklahoma—two states away—and she had to take time off from her retail job. King shakes her head and apologizes that she had to make such a long trip, then tells her to take a few deep breaths. There is small talk; the Beastie Boys’s “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party!)” accompanies the beep, beep, beep of the monitor. Ten minutes later, it’s over. When the patient is cleared to leave, she and her boyfriend get in their car to drive home. It will likely take more than seven hours.

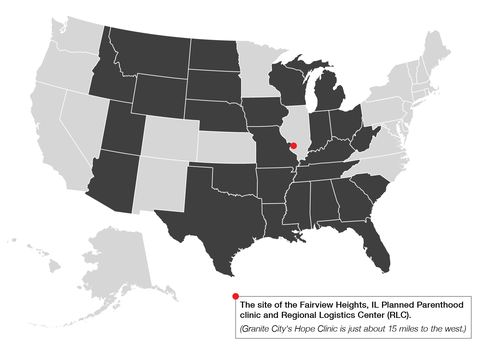

King, a physician, is executive director at Hope Clinic for Women in Granite City, Illinois, just a short drive from the Missouri border—an old steel-manufacturing town in the southwest corner of a state that’s now a blue oasis in the red center of the country. By March, Hope had seen a 20 percent increase in patients since the start of the year, many from more than 100 miles away.

In the wake of an extreme Texas law banning abortions in the state after around six weeks, anti-abortion lawmakers across the South and Midwest have become emboldened, passing a slew of restrictions forcing their own constituents to travel across state lines for care and setting off a ripple effect as clinics fill up and wait times stretch on. The Texas law and the subsequent copycat legislation that has been passed in Idaho and Oklahoma and introduced in Tennessee and other states (the Idaho law has already been blocked in court) are only the latest results of a decades-long, highly organized campaign to ban abortion in the U.S. Since Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, affirming a person’s constitutional right to have an abortion, Republicans have been playing the long game to defeat it, stacking state legislatures and grooming judges who are willing to chip away at abortion access until they can eliminate it altogether. It’s been an effective strategy: Last year, 108 abortion restrictions were enacted in the U.S., the most in any year since Roe, per an analysis by the Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy organization.

King is one of the few providers in the St. Louis area who offer patients a place to go, but the logistics of helping them pay for the abortion and travel costs, as well as navigate flights, cars, and hotels, have drained her staff. It’s a situation that is about to get worse: On June 24, a conservative-stacked Supreme Court ruled to uphold a 15-week abortion ban in Mississippi, overturning Roe and making abortion illegal or highly restricted in as many as 26 states. The stakes aren’t simply high—they are dire.

“As soon as there is no Roe, there will be no more protection for abortion in many states, and it will include most of the states around Illinois,” King says, sipping a coffee in the break room.

Fortunately for the patients who walk through Hope’s doors, King and a small team from the Planned Parenthood about 30 minutes away in Fairview Heights, Illinois, have been preparing for this moment since 2019. That was the year multiple restrictions passed by Missouri lawmakers resulted in just a single abortion clinic remaining open in a state with more than six million residents spanning almost 70,000 square miles.

The impact was immediate, and King says she and her staff were caught off guard by the sudden surge of patients. They worked overtime, but they couldn’t help everyone—a reality that left King heartbroken. “In a lot of cases, there is nowhere else for them to go,” she says.

The memories of those turned away have stayed with King. She remembers the panicked phone calls and the anxiety in their voices. King also thinks about how not being able to get an abortion might have impacted their lives. “It’s all the trickle-down effect of not helping someone when they’re desperate for help,” she says.

King vowed then that when Roe was eventually challenged—as she suspected it would be—she would be ready. Her colleagues at the nearby Planned Parenthood were thinking about the same thing. The group came together to hatch a plan. Missouri was only a preview. If they were going to be a safety net for patients who couldn’t access abortion where they lived, they needed not just more resources but a new model of care.

For patients in states with harsh restrictions, getting an abortion has for years been a logistical nightmare. Some states require mandatory waiting periods of up to three days between an in-person consultation and the procedure itself, forcing the patient to take multiple days off work, plan for extra childcare, and make two trips to and from the clinic. That process is made even more complicated in states mandating that the same provider conduct the consultation and procedure—a challenge in areas of the country where doctors are flown in for short stints.

As more bans are passed, trying to get an abortion can now look something like this: A woman in Oklahoma, where there is a 72-hour waiting period and mandated counseling, calls the nearest clinic to schedule an appointment. She is told that there is a three-week wait since so many patients from Texas are now booking there. She searches some more and eventually finds a provider in another state. That clinic can take her, but now, on top of the cost of the abortion, she needs to come up with extra gas money, hotel costs, and childcare. She calls various abortion funds—organizations that help patients with immediate costs related to abortion care—to try to find enough money to cover what she can’t afford. Before she even sets foot in a clinic, which is likely in a town she’s never been to before, she’s stressed and exhausted. Worse, having to clear so many hurdles in the way of care can make her feel like she’s doing something wrong. “There’s already that level on them of What I’m doing is somehow not a medical procedure that’s safe or that’s more dangerous for me than if I went to go see my doctor for anything else,” says King. The restrictions passed by anti-abortion lawmakers reinforce this message. “They’re also telling them that they’re bad people: You have to go away from here, far away, and oh, by the way, you’ve had to put in all this work to construct this little package so that you can travel and you can get away.”

Yamelsie Rodríguez, the president and CEO of Reproductive Health Services of Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region, proposed an idea: What if, rather than having to call a bunch of different clinics and abortion funds to try to piece together care and financing, patients could call one number? What if the person on the other end of the line could also book them a flight and a room in a nearby hotel, help with childcare costs, and make sure a car is waiting at the airport? In the absence of the ideal scenario, where abortion is readily accessible, what if they could give patients back the choice that some lawmakers were trying to take away?

Colleen McNicholas, Planned Parenthood’s chief medical officer for the region, and Kawanna Shannon, the director of patient access, were on board. So was King.

The group began plotting what it dubbed the Regional Logistics Center, or RLC, a call center attached to Planned Parenthood’s 18,000-square-foot Fairview Heights facility. They knew they didn’t need to reinvent the wheel; they just needed to make it spin more efficiently. There was a wide network of local abortion funds that had been helping patients pay for medical and travel costs for decades, but rarely could one fund cover all of a patient’s expenses. (According to a representative from the National Network of Abortion Funds, a typical contribution from one is $215, while the cost of an abortion ranges from about $500 to $3,500.)

The RLC would coordinate funding for patients while also booking their appointments and arranging their travel. Crucially, the center would support both Planned Parenthood and Hope Clinic patients, casting as wide a net as possible to catch the impending influx of people from surrounding states seeking an abortion. Last year, about 6,000 patients were treated at Planned Parenthood’s Fairview Heights location. If the Supreme Court upholds the Mississippi ban, Rodríguez projects that the number of patients seeking care in southern Illinois will reach 20,000.

“Really, it’s about having those funds as allies and then also our own people that are specialists in this region—like, ‘What hotel is down the street?’ ” says King.

Hope Clinic had partnered with hotels in the past, only to have the business change ownership or management, and “suddenly they don’t have rooms or the rooms are more expensive.” RLC staffers would know which hotels to book or avoid. Hopefully, over time, Rodríguez’s team would also be able to establish partnerships with travel-booking companies and ride-sharing apps instead of heavily relying on donors—which, as of this spring, include billionaire philanthropist MacKenzie Scott. (So far, corporate partnerships have proved challenging. Plenty of companies speak out in support of abortion access, but that doesn’t necessarily translate to a public-facing relationship with a provider.)

Initially, the RLC was slated to open this spring, but the Texas ban pushed the team into a soft launch late last year. Suddenly, calls started coming in from not only Texas but also Kentucky, Arkansas, Tennessee, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma. The center officially opened in January, and yet by March, it still had the feeling of a place coming together. The air smelled of new carpet. The doors to the private offices had yet to arrive. Other than framed prints bought on Etsy—including a drawing of pro-choice advocates above the words “abortion is a human right”—it looked like any other office: gray floors, white walls, a small maze of cubicles. The work of the RLC might at first seem as mundane as its looks—until the phone rings with someone who might otherwise not have gotten care. In those moments, it isn’t simply a call center. It is the front line of a fight.

So far, almost 200 patients are coming through the RLC each month—a number that is expected to increase come June. “It’s going to be a cruel, cruel summer,” says Alexandria Ball, a case manager.

On one unseasonably warm afternoon, Ball is sitting at her desk with a headset on, a light flashing on her phone. When a patient calls in, she books the appointment and then searches a database to find the funds that might be able to help with the costs. “I’m dancing in my chair over here a lot of the time,” she says. “It feels so good, especially if it’s one of those things where it happens really quick. I’m like, Okay, I’ve got to find $2,000 for this patient. Better get to work. And then 20 minutes later, 30 minutes, 45 minutes, I’ve got it down to I just need to find $200. … I’m just like, Oh yeah, okay. Look at me go. She’s wheelin’. She’s dealin’.” (RLC patients receive $1,500 in assistance on average. Most travel more than 250 miles.)

Today happens to be a day when only medication abortions are scheduled. McNicholas, the clinic’s chief medical officer, had expected that given the number of patients coming in from out of state, there would be more demand for in-clinic procedures. So far, that hasn’t played out; roughly 60 percent of all patients come for a medication abortion—even from across state lines. “I am constantly, every day, surprised about the people who get in their car at 3 a.m. from Houston and drive to southern Illinois for me to give them their pill, and they get back in their car and they drive right back to Texas,” McNicholas says.

In-clinic abortions can be more logistically complicated. In February, one of King’s RLC patients from Louisiana was scheduled to start a two-day procedure on a Tuesday afternoon—but didn’t get in until 9 p.m. due to a snowstorm. The clinic was closed that Thursday, so it wasn’t possible to start the procedure until Friday, which meant more nights in a hotel, more time off work. To the relief of King’s staff, the RLC updated the patient’s travel bookings and secured more funding to cover the costs, and she was able to get the abortion. “We just don’t have a ton of time because we’re trying to see patients as they walk in the door, check them in, take them to rooms, help them with their paperwork,” says King. “With the staff at the RLC, we’ve got people literally dedicated to that all day long.”

Rodríguez hopes that clinics serving swaths of the country with few providers and numerous restrictions will see the RLC as a model. She’s also part of Planned Parenthood’s national effort to streamline processes currently slowing them down; as part of that effort, they are working to create a system in which providers willing to fly into havens like Illinois can get the credentials they need to perform abortions there. “If we needed to scale quickly,” Rodríguez says, “how can we invest in technology so we have people not just on call but on shifts that will cover seven days a week, 24 hours a day?”

Bianca, a patient who came through the RLC, clutches a brown paper bag with her discharge papers and her underwear, and she checks to see when the car will arrive at the clinic to take her back to her hotel. She’s just come out of recovery for an abortion in the second trimester, and while she’s relieved, she’s also angry. “If I hadn’t been basically blocked at every turn … I wouldn’t be here today,” says the 33-year-old.

Shortly after learning she was pregnant, Bianca (who requested a pseudonym to protect her privacy) searched online for where to get an abortion near her town outside Kansas City, Missouri. She booked an appointment with the first place that came up—a self-described “pregnancy resource center” that advertised “preabortion screenings” on its website. (Pregnancy resource centers, or crisis pregnancy centers, as they’re often called, don’t actually provide abortion care but instead try to dissuade patients from having abortions at all.) A staff member conducted an ultrasound and described the embryo in detail, against Bianca’s wishes. “I said, ‘Please, have the sound off and don’t have the monitor on. I don’t want to see anything or hear anything,’ ” says Bianca, who was about eight weeks pregnant at the time. “She had the audio off, but she proceeded to tell me how many inches it was and ‘Oh, nice strong heartbeat.’ I had my eyes squeezed tight to be sure I didn’t see anything.” Bianca reiterated that she wanted to have an abortion and says the staff informed her they did not do abortions there. She left with a few pamphlets and little hope. “I felt like, Oh, I have to surrender.”

The staff there continued to call and check up on her, which made Bianca uncomfortable, but she also didn’t know where else to go. Eventually, she started searching for clinics in other states and contacted them for an appointment. One asked for fetal measurements, so she decided to return to the crisis pregnancy center; they had performed an ultrasound before, so she assumed they’d be willing to do it again.

When Bianca asked for the measurements, however, they told her they would not print them out. “I was like, ‘That’s fine. When you do the ultrasound, I need this number and this number, so just tell me and I can write them down. No biggie,’ ” she says. That’s when the vibe in the room shifted. She went to leave, and several staff members came to talk to her in the hallway. “The women in that clinic surrounded me, and they were basically reiterating that they don’t do abortion referrals but they were very neutral and were there to support whatever decision I make,” says Bianca. It felt like an intimidation tactic. She left confused, exhausted, and without the measurements she came for.

Time ticked on, and Bianca’s options dwindled. By that point, her pregnancy was past the 11-week mark, so a medication abortion was no longer a possibility. She didn’t have the money to travel, and even if she did, she didn’t know who would take her. She also couldn’t ask her conservative relatives for help, she says. It felt like being trapped in her own body. “It just got to the point where I wanted to crawl out of my skin,” says Bianca. “It felt like I had no choice.” She started journaling to sort through her feelings, at one point writing, “You have nobody to talk to and nobody who will support you. Loneliest, scariest, most difficult experience ever.”

Finally, Bianca contacted the only abortion clinic in Missouri, a Planned Parenthood in St. Louis, which is a six-hour drive from her home. (She had to scroll down her search results to find it; the crisis pregnancy center appeared at the top.) A receptionist told her she was no longer eligible for an abortion in the state—but offered another option. There was a Planned Parenthood clinic just over the border in Illinois, she said, and a representative from its new logistics center could help with funding and travel arrangements. “Would you like me to transfer your call?”

When Ball, the case manager, picked up, she booked Bianca’s appointment and then offered to arrange flights and car service for her and her son, get them set up in a nearby hotel, secure food vouchers to cover meals, and work with abortion funds on her behalf to cover the procedure and related costs—which amounted to more than $3,000.

Bianca was skeptical at first, telling Ball, “I’m really trying not to feel like you’re leading me on.” She didn’t believe it was real until she received a confirmation email that day, which was like “a million blocks” being taken off her shoulders.

Four days later, on a Sunday morning, Bianca put on her comfiest yoga pants and got in a car to go to the airport. During the 45-minute ride, she focused on only the task ahead of her. She would get through security, and she would find the gate. It was her first time on a plane. “I already have a lot of anxiety to begin with, so I was trying to take it one step at a time,” says Bianca.

A car picked her up outside her hotel the next day to take her to the clinic. During the ride, the driver told Bianca he had been there before and was going to bring her in the back way to avoid protesters lurking near the entrance. Once inside the clinic, Bianca soon began the first stage of a D&E, or dilation and evacuation—a procedure that is more invasive and expensive than methods used earlier in pregnancy. At her hotel afterward, she ordered dinner on a food-delivery app using the vouchers Ball had procured for her and lay down. “I just kept telling myself, After tomorrow, it will be smooth sailing,” says Bianca.

The next morning, she underwent the second part of the procedure. The abortion itself was relatively painless, she says; she was given sedation and ample time to recover under a nurse’s supervision. Now all she wanted was to eat something and sleep. She craved her own bed in her own home. Two flights (including a layover in Chicago) and a ride home from the airport later, she finally got to curl up under her comforter and place her head on her pillow. It was over.

Until Bianca tried to get an abortion where she lived, she didn’t realize that lawmakers—bolstered by an anti-abortion movement that had been snowballing for years—had already made it nearly impossible. That’s not uncommon, says King, who also works at a group ob-gyn practice in Missouri. There, “I still see patients who are pregnant and say, ‘Oh, I’ll just go wherever because I need to access abortion care or I need to go do this,’ and I look at them like, ‘No, no, you won’t, because that’s not happening in Missouri,’ ” she says. “They look so shocked at me, like, ‘What are you talking about? How did this happen?’ ”

Just as soon as the RLC is up and running, ready to help patients like Bianca who can’t get care where they live, anti-abortion lawmakers are already trying to shut it down. In March, Missouri state representative Mary Elizabeth Coleman, a Republican known for her anti-abortion stance, continued to push a measure that would allow private citizens to sue anyone who helped a person get an abortion in another state.

That proposal, the first of its kind, was ultimately omitted from the bill passed by the Missouri House in April. That legislation combined provisions introduced by multiple lawmakers—including one to defund Planned Parenthood in the state and another that makes prescribing or even delivering abortion pills in violation of state law subject to the same penalty as trafficking illegal drugs. In April, Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt signed a bill into law that makes it a felony to perform an abortion in the state, with an exception only when the pregnant person’s life is in danger. Even though the law is expected to be challenged in the courts before it goes into effect, it still serves to further stigmatize abortion care and confuse patients. “We saw the same thing happen when there was a lot of publicity around the bans in Missouri,” says King. “We saw patients from Missouri, Illinois, and other states asking a ton of questions about Can I get an abortion? Am I going to get arrested? Am I going to jail? Are we going to jail? Are the doctors doing something illegal?” People see news coverage of bans and restrictions and aren’t sure what it means for them; even a proposed ban can cause panic.

Bianca is now fully tuned in to the imminent threat to reproductive rights. More than a month after her procedure, she too has her eyes set on SCOTUS. “I just wish they knew that women who are as determined as I was to get [an abortion], they are going to do it regardless,” she says. Recent data suggests Bianca is right: The vast majority of people denied abortions in Texas went on to have them anyway, according to two studies by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin. By the end of last year, an average of nearly 1,400 Texans were leaving the state for abortion care each month.

King and the team at Planned Parenthood were ready for those patients this time around—and they plan to be there for whatever comes next. On that same day in March when she saw patients from Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Missouri, King raced up and down the stairs of Hope Clinic in her scrubs, ping-ponging between administering medication abortions in private offices and performing abortions in operating rooms. By the end of her nine-hour workday, she’d seen about 30 patients.

King can’t control what SCOTUS decides, but she can help people get to Hope and get abortion care. “What the RLC and these individual funds are doing—they’re saying, ‘Okay, but what can we do for you today? What can we do for you just to take one little burden off of the many things that you’re already facing in your life?’ ” she says. “That’s really important.”

Want to help keep abortions safe? Donate to an abortion fund, like the ones that fund the RLC, today. You can also donate directly to the RLC here.

*This story, originally published on May 7, 2022, has been updated to reflect that on June 24, 2022 the Supreme Court voted to overturn Roe v. Wade.